I recently had a number of conversations with CEOs of later-stage startups (generating significant revenue) that went something like this. They want to raise more money, and VCs are offering them money at a high valuation. The CEO is worried that taking money at that valuation will “set the bar too high” and make it difficult to sell the company – if the time comes when he/she thinks it makes sense to sell – at a price that isn’t a significant multiple of that valuation.

These CEOs are worrying too much. VCs know what they are doing and almost always invest with a financial instrument – preferred shares – that protects them even when the valuation is very high. **Preferred shares behave like a stock on the upside and a bond on the downside. **The only way investors actually lose money is if the company is sold for less than the amount of money raised (which is generally significantly lower than the valuation).

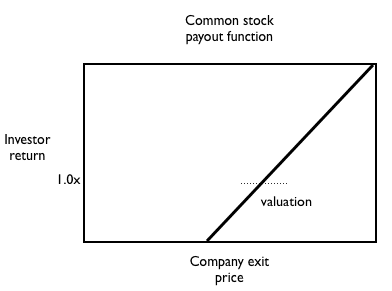

Here is what the payout function looks like for common stock (for example, what you get when you buy stocks in public markets):

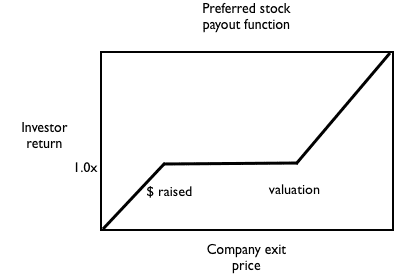

And here is what the payout function looks like for preferred shares:

So, to take a concrete example, Dropbox reportedly raised their last financing at a $4B valuation*. If you think of this as a public market valuation of common stock, you might think this means the VCs are betting $4B is the “fair value” of the company, and will lose money if Dropbox’s exit price ends up being less than $4B. But in reality, assuming the standard preferred structure, the last round investors’ payout is as follows :

Scenario 1: Dropbox exits for greater than $4B ==> investors get a positive return (specifically, exit price divided by $4B)

Scenario 2: Dropbox exits for between $257M (total money raised) and $4B ==> investors get their money back (possibly more if there is a preferred dividend)

Scenario 3: Dropbox exits for less than $257M ==> investors lose money

If reports are true that Dropbox is profitable and generating >$100M in revenue, then scenario 3 – the money losing scenario – is extremely unlikely.

Will investors be thrilled with scenario 2? No, but they are pros who understand the risks they are taking.

Going back to the entrepreneur’s perspective, in what sense is a high valuation “setting the bar high”? In the preferred share payout model, there are two “bars”: money raised and valuation. I don’t see any reason why entrepreneurs shouldn’t be as aggressive as possible on valuation, especially if they are confident they won’t end up in scenario 3.

An important point to keep in mind is that, in order to maintain flexibility, entrepreneurs shouldn’t give new investors the ability to block an exit or new financings. Investors can get this block in one of two ways – explicit blocking rights (under the “control provisions” section of a VC term sheet) or by controlling the board of directors. These are negotiable terms and startups with momentum should be very careful about giving them away.

* Note that I have no connection to Dropbox so am just assuming standard deal structure and basing numbers on public reports. I am making various simplifying assumptions such as not distinguishing between pre-money and post-money valuation.